Animal Dental Clinic

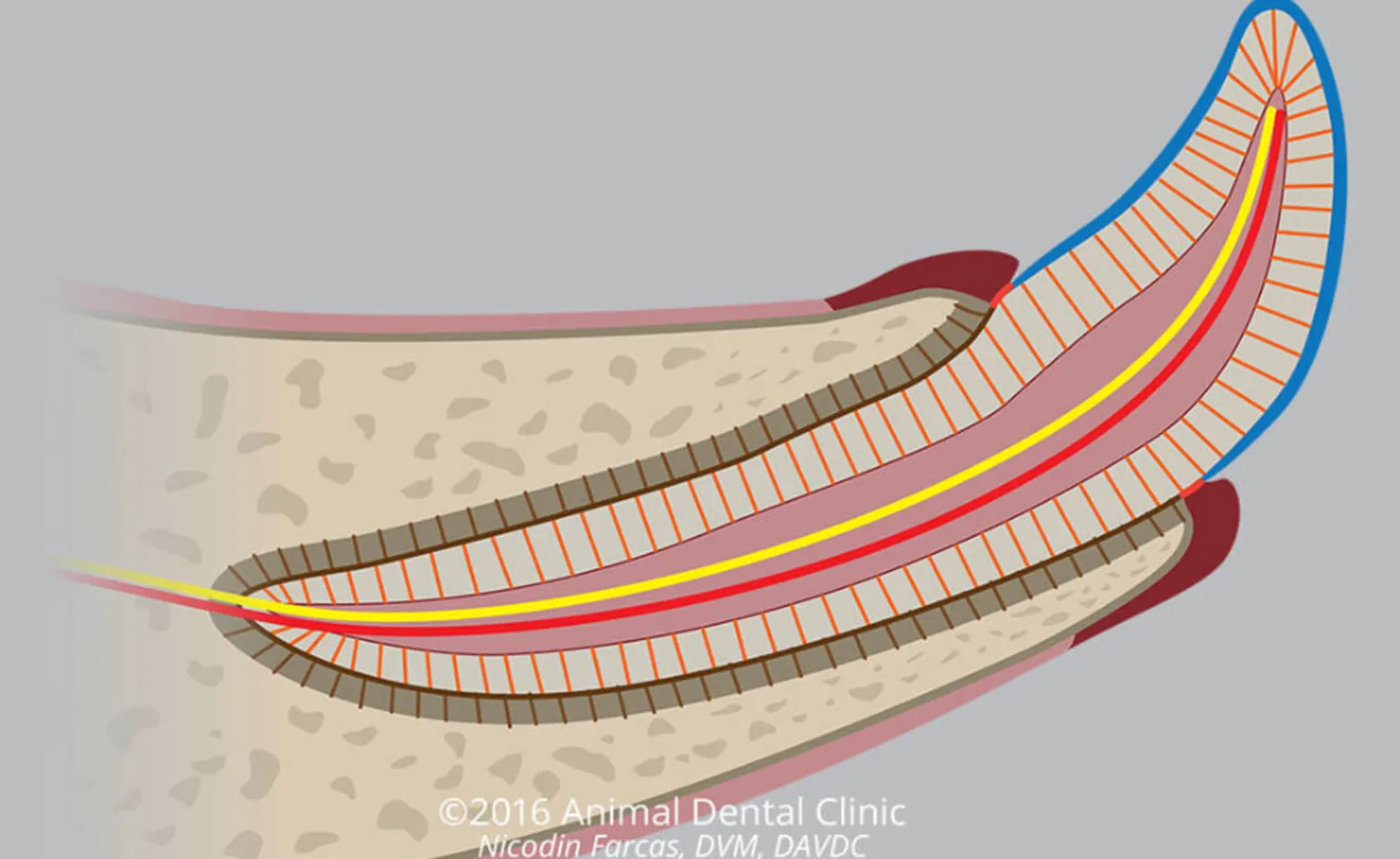

Periodontal tissues surround and support the tooth root.

Four main components comprise the periodontal tissues: the gingiva, the periodontal ligament, the alveolar bone, and the tooth cementum. When these tissues are damaged due to the interaction of oral bacteria and the local immune reaction, periodontal disease, ranging from mild to severe, is the result.

Periodontal Structures & Supporting Tissues

The periodontal tissues each have a distinct function.

Teeth are secured into the alveolar bone by the periodontal ligament, which attaches the cementum of the tooth to the alveolar bone.

The gingiva forms a gasket-like seal around the tooth. It is attached to the tooth by a vulnerable, thin, tissue called the junctional epithelium and gingival collagen fibers. Gingiva represents the first line of defense of the tooth root against invasion by oral bacteria.

Dental Plaque

Dental plaque is the source of bacteria that causes periodontal disease.

The oral biofilm, or plaque, is bacteria and their sticky, malodorous, products. The biofilm attaches firmly to teeth and protects bacteria against antibiotics and actions of the local immune system. This is the cause of bad breath and is relatively easily removed mechanically (with toothbrushing).

The oral bacteria are constantly trying to invade oral tissues and are countered by the local immune system. The first place this interaction occurs is at and around junctional epithelium (where the gingiva attaches to the tooth), or in places where the normal oral barrier has already been disrupted.

If the oral bacteria do manage to cross the oral barrier and establish infections, the infected tissues require periodontal surgery to remove the biofilm to allow healing, followed by restoration of the oral barrier by suturing the gingiva and mucosa.

Long-term management of periodontal disease once it has been treated, requires routine oral hygiene.

Dental Calculus ("Tartar")

A red flag.

Minerals from saliva are deposited and crystalize in dental plaque on the tooth surface to form calculus, which is a hard brown deposit that can’t be brushed away. Certain teeth, including teeth that are less or non-functional due to disease, tend to build more calculus.

On its own, calculus isn’t a disease. However, it often signals the existence of periodontal or other oral diseases and can contribute to disease progression. While the oral bacteria present in dental plaque are fast to adhere to the clean tooth, the rough surface of calculus allows bacteria to attach more easily.

While simply removing visible calculus by scaling teeth (without treatment guided by oral diagnostics) may appear to be beneficial, it can allow the existing diseases to progress undetected.

Diagnosis of Periodontal Disease

Our pets develop periodontal disease when dental plaque invades the periodontal tissues.

When the oral barrier is under constant pressure by accumulating dental plaque, that barrier can break down, which allows oral bacteria to infect the periodontal tissues that surround and support the tooth. This initially causes gingivitis, which then can progress to periodontitis.

On awake oral examination, gingivitis is diagnosed based on observing swelling, redness, and bleeding of the gingival tissue. Beyond this, to determine the extent and severity of periodontitis, the patient should be anesthetized for dental radiographs and periodontal probing.

Stages of Periodontal Disease

Understanding whether periodontal disease is mild or severe is important for planning treatment.

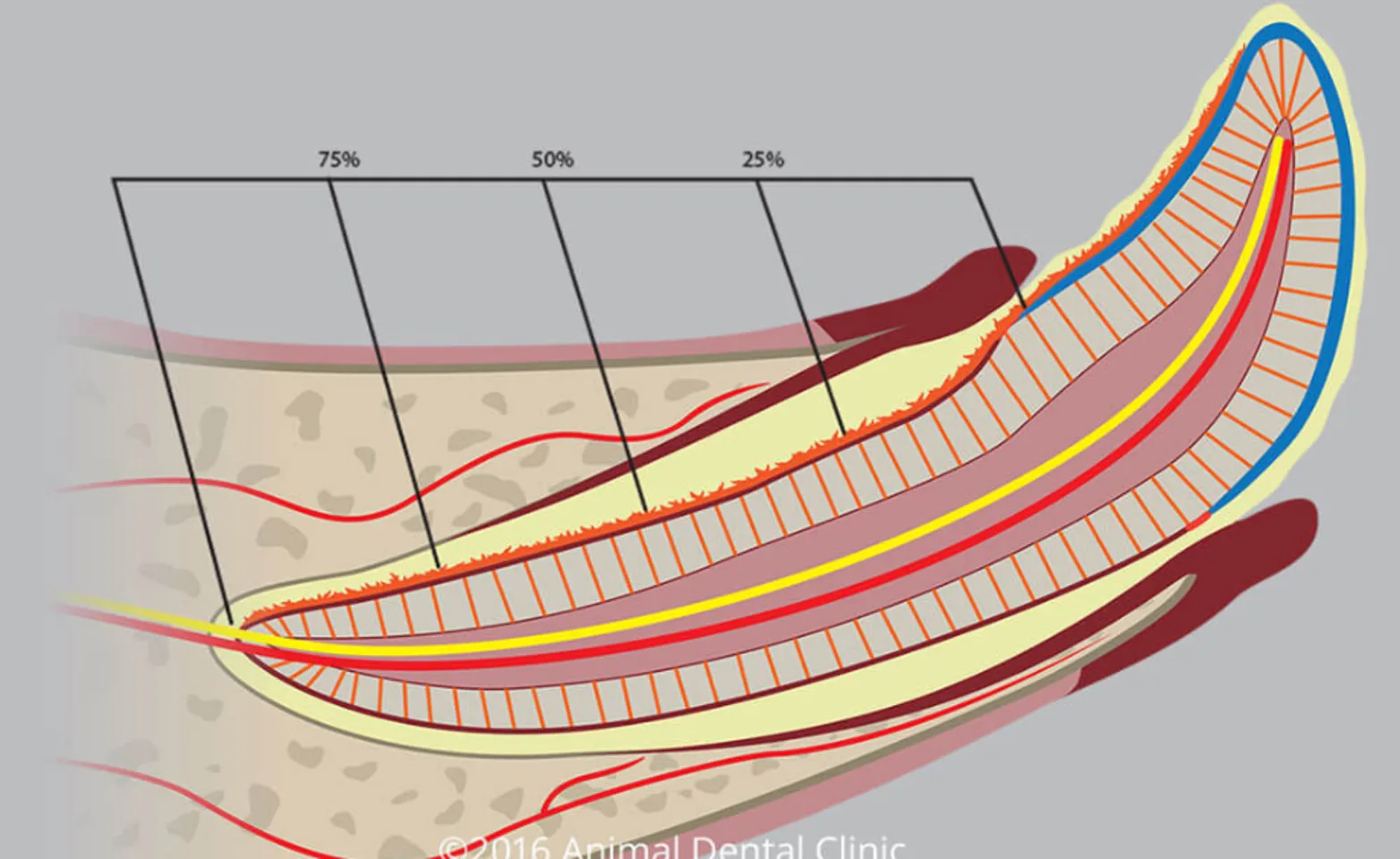

Periodontal disease is progressive, meaning that it begins with mild changes, but gradually increases in severity. Initially, in stage I, gingivitis is the only manifestation. Beyond this, in stages II-IV, the periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone that support the tooth are damaged. This damage, if left untreated, can result in loss of affected teeth, as well as complications when infection extends beyond the oral cavity.

Image Information: Inflammation of the gingiva (gingivitis; dark red) as a result of interaction between dental plaque (light yellow) and local immune response brought by increased blood supply to the periodontal tissues (red). Calculus (jagged orange line) has covered part of the tooth. In this illustration, destruction of the junctional epithelium (solid orange line shown on the opposite side of the tooth) has progressed to periodontitis, with destruction of the entire periodontal ligament and the complete loss of the alveolar bone surrounding the tooth root (stage 4 periodontitis).

Treating periodontal disease often involves more than removing plaque and calculus.

“Teeth cleaning” describes the procedure of removing plaque and calculus by scaling and polishing the teeth. A technical term for this is “dental prophylaxis.”

This is an appropriate treatment on its own when the patient does not have periodontitis and no other treatment is necessary. This determination requires dental radiographs and periodontal probing. Simply performing teeth cleaning without looking for and treating any underlying disease is of little to no benefit and can even be harmful.

When periodontal disease is diagnosed, treatment involves safely cleaning the tooth roots and restoring the oral barrier. These are achieved through several types of procedures, including root planing, subgingival application of locally-acting medications, tissue grafting, and surgical closure of sites of periodontal disease. When periodontal disease is advanced, tooth extraction may be the only option to restore the patient’s mouth to a functional and pain-free state.

As much as it is our goal to save teeth wherever possible, when periodontal disease becomes severe, the goal shifts from saving teeth to saving jaws (by preempting fracture), as advanced periodontal disease is a common cause of jaw fracture, especially in small breed dogs.

Following treatment of periodontal disease, or before it develops, beginning a daily oral hygiene routine, which includes tooth brushing helps to maintain oral health, though routine veterinary visits are still necessary.